- Mobile Content Is Twice as Difficult

- If in Doubt, Leave It Out

- Defer Secondary Information to Secondary Screens

- Mini-IA: Structuring Content

Mini-IA: Structuring Content

The definition of mini-information architecture (mini-IA) is simple: It’s how you structure the information about a single topic. For example, the mini-IA of an email message is a single page.

When something is covered on a single page, we don’t usually think of the presentation as “information architecture.” However the very decision to stick to a single-page format is an IA matter.

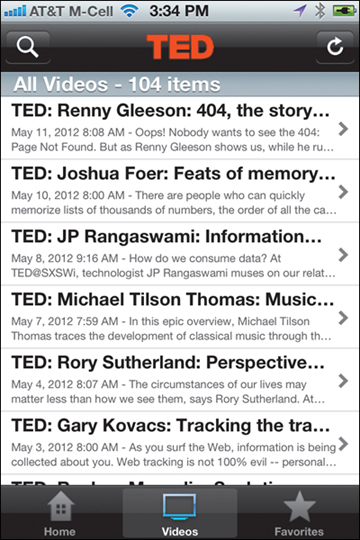

Often it’s better to break up information into multiple units rather than using an overly long linear flow, like that shown in Figure 4.18. You can then present these multiple units across a few pages or use a within-page navigation system, such as tabs or carousels.

Figure 4.18. Ted Video for iPhone. All the 104 available videos are presented in a long list. A mini-IA grouping of videos on topics would have been more helpful.

Linear Paging? Usually Bad

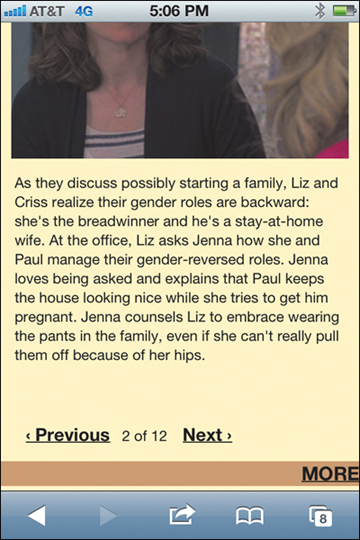

Let’s first dismiss a popular mini-IA as being almost universally bad for usability: If you have a long article, it’s almost never good to do as NBC does in the example in Figure 4.19 and simply chop it up into a linear sequence of pages. If the only navigation is a “Continue” or “Next page” link, it’s typically better to stick it all on a single page and rely on scrolling instead of page turning. Not only do users have to wait for a page to load every half a minute or so, but should they want to go back to the list of episodes when they finish reading the summary, they would need to tap the browser’s Back button 12 times.

Figure 4.19. NBC’s mobile website (m.nbc.com) splits episode summaries into many pages with just a picture and a paragraph per page.

(The exception here is for content presented on tablets, such as the iPad, or for book-reader apps where the swiping gesture provides a generic command for moving between pages and/or the content is preloaded, so it doesn’t take any time to move between pages. Also, books are not usually read in a single session, and having the book split into pages makes it easier for users to keep their place in the book; otherwise, imagine having to scroll through an entire book to find the third paragraph in Chapter 11.)

In many situations the best alternative is to chunk information into individual content units, focusing on logical cohesiveness. You can then describe each unit accordingly and let users navigate directly to the unit that meets their needs. (Note that “page 2 of 12” is neither descriptive nor deserving of its own page.)

(For wizard-style interactions, such as e-commerce checkout, a linear page-turning progression usually works better because even though each step is logically cohesive, they’re in an application workflow, so you can’t go to step 3 without first completing step 2.)

Alphabetical Sorting Must (Mostly) Die

Another popular mini-IA that is often misused is alphabetical ordering. Sorting a list of options alphabetically has two main benefits:

- If users know the name of what they want, they can usually find it in the list pretty quickly.

- Lazy design teams don’t have to work on figuring out a better structure. Because we all know our ABCs, anybody can put the items into the correct sequence.

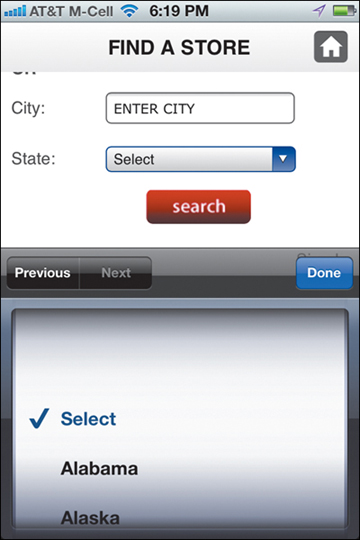

The first point is a true benefit, and alphabetical sorting works fine in some cases. For example, it’s usually easy enough to pick out a state from an alphabetical list of the 50 U.S. states. Indeed, in this case an alpha listing is more usable than, say, grouping the states by region or showing them on a map–at least when users need to click only one state (usually their own) to navigate to a page with state-related information.

(Listing states alphabetically is a good choice only when people have to select one state from a menu for navigation or a command. When users need to specify the state as part of their address–as in e-commerce checkout forms–it’s better to present a text field where people can type the two-letter abbreviation. This is faster and less error prone; on mobile, it also avoids the need for prolonged scrolling within a small drop-down box that spans only half of the tiny Phone screen, as in Figure 4.20.)

Figure 4.20. Macy’s app for iPhone. Selecting a state from a drop-down box is inefficient.

Lists of countries and other known-item problems are also often fine to alphabetize. However you do need to ensure that users will know unambiguously the name of their selection. If people have to look at several places in the list, you’ve defeated the purpose of the A–Z order.

For most questions, either:

- Users don’t know the name of what they want, making A–Z listings useless,

or

- The items have an inherent logic that dictates a different sort order, which makes A–Z listings directly harmful because they hide that logic.

Sizes are ordinal data, meaning that they have an inherent monotonically increasing sequence. Such items should almost always be sorted accordingly.

Other times, items have domain-related logical groupings. You can often determine this underlying logic in a card-sorting study where you ask users to group related items together.

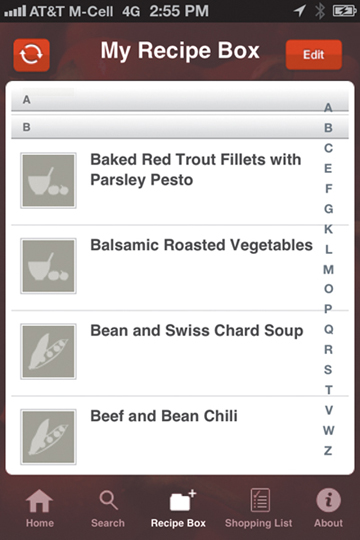

For example, Epicurious is a recipe app that allows users to search and save recipes (Figure 4.21). The list of favorite (or saved) recipes can be seen in alphabetical order or in recently added order. Neither works for a long list of recipes. In the case of alphabetical sorting, the first word of a recipe name (such as, “Balsamic” for “Balsamic roasted vegetables”) is often nonindicative of the recipe. And except for very recent recipes, users are unlikely to remember when they’ve added a recipe to their list for the first time. (To add insult to injury, Epicurious does not have a search function for the recipe box, making it very difficult for people to deal with a large number of recipes.) A mini-IA that grouped recipes under different categories (fish, meat, desserts, etc.) would have been a lot more useful.

Figure 4.21. Epicurious for iPhone. The list of favorite recipes can be sorted in alphabetical order or in recently added order. Neither of these is appropriate for long lists of recipes.

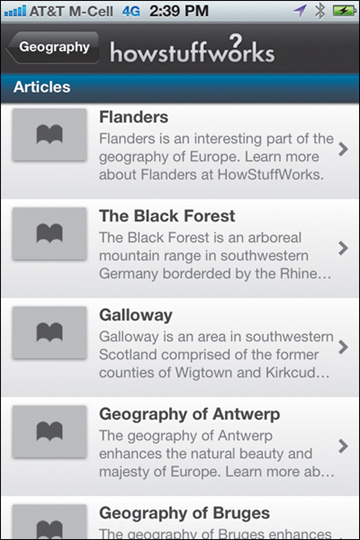

Timelines and geographical location are other groupings that are often useful, although sometimes they can go wrong, too, as shown in the example in Figure 4.22. The entries in the list are geographical locations, but the editors had their own understanding of alphabetical order: The Black Forest is under “F” (presumably for “Forest”), and Antwerp is under “G” (for “Geography of Antwerp”). It’s very unlikely that users could guess at this type of classification; in fact, when searching for Antwerp, they’ll probably just stop at “A,” thinking that it shouldn’t appear farther down the “alphabetically” ordered list.

Figure 4.22. How Stuff Works app for iPhone. Here’s an example of alphabetical order gone wrong: Antwerp is under “G” (for “Geography of Antwerp”).

You can let the importance or frequency of use guide how you prioritize long listings rather than default to less-useful alphabetical sorting.

Depending on the nature of your information, usability might be better served by yet other types of structures. And yes, in a few cases, this might even be the alphabet. But typically, when you reach for an A–Z structure, you should give yourself a little extra kick and seek out something better.

Example: Usage-relevant Structure

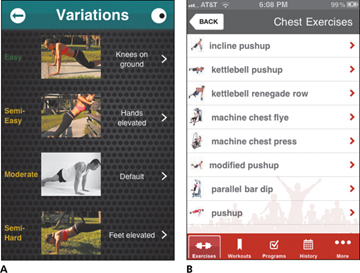

To illustrate a usage-relevant structure, look at Figure 4.23, which shows two example structures that present information about exercises in a mobile fitness app.

Figure 4.23. Lists of exercises in two iPhone apps: (A) You Are Your Own Gym and (B) Full Fitness.

The example in Figure 4.23A employs a useful mini-IA for push-up exercises: It puts all the exercises together in a list that’s ordered from the easiest to the hardest. In contrast, the example in Figure 4.23B sorts the exercises alphabetically, which, as discussed in the previous section, is usually a poor structure.

The Full Fitness screen shot (Figure 4.23B) shows only a part of the complete list and includes incline push-up, modified push-up, and plain old push-up. How do you know which one to pick if you want a variation that’s a bit more challenging than your last exercise? Is “modified” easy or difficult?

“Modified” obviously emits poor information scent: The word tells you what the exercise is not instead of what it is. “Incline” is better, though not as clear as the equivalent “hands elevated” label used by You Are Your Own Gym. Quick, what’s the difference between an incline push-up and a decline push-up? We bet you can’t answer that as quickly (or as correctly) as you might decipher “hands elevated” versus “feet elevated.” Simpler words are usually best. (You’re excused from preferring simple words if you’re writing for an expert audience. But advanced fitness enthusiasts definitely won’t need to look up how to perform an incline push-up, even if that’s what they might prefer calling this exercise.)

The designers of Full Fitness would have surely benefited from reading this chapter. That said, their main problem is structural. Even with improved labels, the current Full Fitness scheme would remain less usable than the You Are Your Own Gym solution, which recognizes that push-up variations deserve their own mini-IA structured according to the best way to make sense of different push-up exercises (here, progressing from easy to hard as you get stronger).

As an aside, both apps use thumbnail photos to further explain the exercises and help users determine which one to choose. And both have usability problems. Except for the “moderate” photo, You Are Your Own Gym’s photos have too much background detail to be easily understood given their small size. Full Fitness’s photos are cleaner and almost as easy to grasp as the Own Gym photos, even though they’re much smaller. We usually criticize tiny thumbnails, but most of the Full Fitness images (except for the two machine exercises) are clean enough to adequately differentiate the exercises.

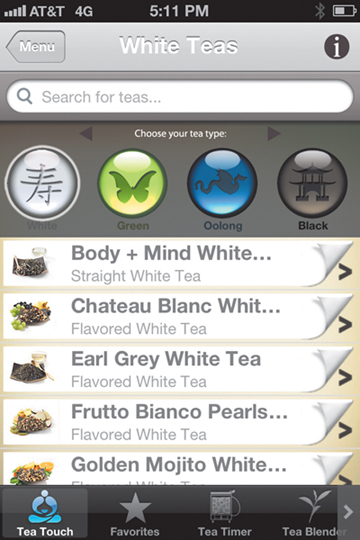

Another example of good mini-IA comes from Teavana (Figure 4.24). Teavana splits its teas by type (white, green, oolong, and black). Interestingly, Teavana implements its mini-IA in a slightly different way than You Are Your Own Gym (see Figure 4.23A): Teavana’s mini-IA is not given a separate page; instead it’s shown in a persistent strip (that doesn’t disappear as the user scrolls down through the list of teas) at the top of the tea list. This solution sacrifices some screen space, but it lets users change the tea type more efficiently. However the thumbnails are small and hardly necessary: It’s unlikely that anybody would recognize or select a tea using that kind of image (or, perhaps, any image at all.)

Figure 4.24. Teavana app for iPhone. Teavana appropriately uses a mini-IA for its tea list. The top panel with the four types of teas is persistent.

Usage-driven Structure

When you have a lot of information about a topic, there are three ways of presenting it:

- One long page. One long page is a simple choice but makes it harder for users to access individual subtopics. You also risk intake fatigue as users slog their way through the page to the bitter end (and many will give up before the going gets too bitter).

- Mini-IA. Mini-IA lets you split the info into appropriate chunks. This allows direct access to subtopics of interest and can give users a better understanding of the concept space than they’d get while putting their nose to the grindstone to endlessly scroll.

- Distributed information. Distributed information lets you blend together subtopics of many topics, as in the push-up exercises, cable machine exercises, and so on in the Full Fitness section on “Chest Exercises” (Figure 4.23B).

Here we’ve argued that usability is often enhanced by the second approach. However, a mini-IA makes sense only if you can structure this localized information space according to a principle that supports the users’ tasks and mental models.

Since the Web’s beginning, internally focused structuring has been one of the most user-repellent design mistakes. Our research into intranet IA, for example, has repeatedly found that both usage and employee productivity skyrocket when a department-based IA is replaced by a task-based IA.

Along similar lines, a mini-IA won’t help if it’s structured according to your internal organizational chart or any other way that fails to match how customers want to access information. But if you embrace a mini-IA–identifying a usage-based structuring scheme as a basis for a clear and modest navigation system–you’ll likely have a winner on your hands.