Five Critical Techniques for Creating Seamless Photoshop Composites

Compositing in Photoshop can be nothing less than pure digital fun—especially when you have the right tools and techniques to use. I personally find compositing addictive, much like a good book or computer game, but with one major difference: Playing in Photoshop, you don't just come away with a high score or memorable story; instead, you have a tangible and creative accomplishment you can share with the entire world.

Much like when mastering any game or developing a solid skillset with any type of technology, you might be frustrated by not always being able to do what you want or get great results when compositing in Photoshop. The craft of compositing is not easy. However, in this article, I'll help you to develop skills in the craft by describing my top five compositing strategies—giving you my hard-earned advice for creating imaginative and seamless composites. Learn how to make it fun instead of frustrating!

Match the Lighting When You Shoot

Surprise! Compositing begins with shooting photographs, not just jumping straight into Photoshop. Composited shots look best with perfectly matched lighting. When the lighting doesn't match, the viewer's "fake-o-meter" tends to skyrocket—generally something you want to avoid at all costs. Luckily, matching the lighting just takes planning, preparation, and strategy. Overall, there are several things to look out for when shooting your own composite material and getting the lighting to match, but it mostly boils down to light quality and direction.

Assuming that you're shooting your own material, I suggest that you first figure out and match the quality of the light between all the different shots you want to use in a composite. Does the lighting look soft and diffused? Or is it harsh direct light with high-contrast shadows? The quality of lighting has to match between the various combined shots in some way. Though you can sometimes paint in your own lighting (if you have a good eye for it, and you shot everything under fairly soft lighting), you'll get the best results by matching the shots as much as possible before bringing them into Photoshop. This preparation enables you to take the imagery to another level once in editing. In the end, you won't have to work nearly as hard.

With the light quality determined, obviously the direction of the light also matters a great deal. If you're using multiple light sources, be aware of the direction of the key (main) light, fill, and any other highlights; as well as backlighting, sidelights, spotlighting, and so on. At the very least, I suggest taking a look at some lighting tutorials, as they can be of great use in this regard. You can do quite a lot inexpensively, unless you're interested in paying your pinky finger and right foot for fancy lighting gear. Overall, pay close attention to the lighting sources and match them as best you can between the shots.

Depending on the kind of composite you're creating, lighting can vary dramatically. Generally speaking, when shooting indoors, cheap flashes diffused with paper or bedsheets can do wonders—or even clamp lights with compact fluorescent bulbs. Shooting outside? Large pieces of half-black and half-white foam core board can help you to block light or bounce it the way you need it to go. In either case, control and planning are the keys to getting light quality and direction to match.

Use a Tripod and an Intervalometer

Depending on the type of compositing you're doing (such as my "Raising a Super Child" series, or something similar), two pieces of equipment are invaluable. A tripod prevents the camera position from moving, and an intervalometer (a fancy word for a camera trigger with a built-in timer) lets you shoot continuously without touching the camera—or even having to be behind it, for that matter. (Plus, this device looks cool and mighty impressive!)

Figure 1 shows an example from a recent family vacation composite I created called "Look, Mom!" to help illustrate this point. Using my Canon 7D for this image, I combined five specific shots, all taken from the same point of view, thanks to the tripod I insisted on hauling along through the entire trip abroad (just in case a moment like this came up). Then I hooked up my flux capacitor—sorry, intervalometer—to take pictures at regular intervals that I specified to ensure a good amount of variety.

Figure 1 'Look, Mom!' (2014) shows the potential of combining both a tripod and intervalometer to piece together just the right images to make the impossible seem possible.

The tripod ensured that all the shots matched up perfectly, without my having to readjust the camera position or do any guesswork. The major benefit of using the tripod comes once the image is opened in Photoshop. You just copy a choice selection in the image (in this example, a person such as my mom or my wife) using the Marquee tool (select and then press Ctrl-C or Cmd-C to copy); then, on a blank background image without the subject, paste the person into the same location with Ctrl-V or Cmd-Shift-V. This copy-and-paste operation ensures that the copied material is pasted in the exact position from which it was copied. Since both shots match up perfectly thanks to the tripod, masking or other editing is fairly minimal and takes much less work.

Using an intervalometer allows for total hands-off shooting, giving you the ability to try many variations of poses and positions in front of the automated camera. Even if I'm not capturing the images myself, using an intervalometer lets me stand next to other subjects and give them direction—or hold them up in the air, like the little dude in this example. When shooting composite shots with live animals or children, setting the shot interval for 1–2 seconds can net you at least a couple of usable shots out of the spree. Capturing too few shots might mean having to reshoot (which is sometimes for the best) or using a less-than-optimal pose or two, and ultimately your composite will probably be rubbish. So shoot and shoot some more until your memory card is full; you'll have plenty of shots to use—and (hopefully) your composite will look killer because you've given yourself so many great choices.

Shoot for Variety and Build Your Own Photo Archive with Adobe Bridge

When puzzle-piecing images together from many different sources (as I do in various types of composites), your imagination is the limit—that is, as long as you also have the photographic library to support it! That's why I tend to shoot everything everywhere I go. Whether with a point-and-shoot or my DSLR, I'm always on the lookout for interesting trees, buildings, textures, waterfalls, lakes, animals, and so on. You never know when you'll have an idea that needs a specific kind of material, lighting, or quality; and compositing without the right imagery is like completing a jigsaw puzzle without the right pieces—a lot of forcing that just looks wrong. These days, digital memory is super cheap, so I just keep shooting and collecting. Yes, it's true, I am an official digital image hoarder! But my composites are better because of it.

This massive image archive is really only feasible thanks to Photoshop's awesome library/image-sorting counterpart, Adobe Bridge. Rating images and making what are called "collections" in Bridge helps dramatically with building a useful and searchable archive for massive jigsaw-like compositing. To rate an image in Bridge, select it and then press and hold down the Ctrl or Cmd key while pressing a number, 1 through 5. Show only the highest-rated images by filtering with a click on the small star icon ![]() in the application bar.

in the application bar.

The collections feature in Bridge is actually a tabbed panel loitering on the left side of the default workspace. Here you can create a new collection folder by category, such as Trees, Lakes, People, or whatever you want to name your virtual collection. Think of this feature as leaving your files where you originally downloaded them, but also grouping a few chosen images by subject within another hidden folder seen only by Bridge. Add images to each collection where you think the image belongs; when you click the collection's folder name, you'll see an array of the various "collected" images, like a saved quick-search feature. Need trees for a new composite? Click on your trees collection. Frogs? Try the frogs collection! (Okay, even my frogs collection is fairly sparse—but I think you get the idea.)

Make Good Selections and Mask Seamlessly

There are a few key strategies to try when making selections and masking. The first strategy is pretty general: Practice handling the various selection tools and learn how each works. Knowing when to whip out which tool helps with productivity as well as masking times and quality. I get into the nitty-gritty of each selection tool in my book Adobe Master Class: Advanced Compositing in Photoshop, but in short, you can sum up selections as used primarily for helping with masking—leaving out all the parts you don't want seen, while keeping visible every finger, toe, and even hair strand you want to show. Sometimes (such as when compositing landscape scenery), I'll even skip the selections part and jump straight into painting organically on a mask.

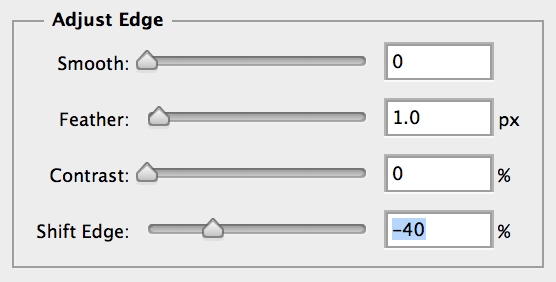

Even with seemingly good-looking selections and proper tool use, once you apply a mask to a layer, it might look "off" for unexplained reasons. This is because our eyes know when something isn't right, even if the brain can't pinpoint the problem. The main kicker for just about all masking is to match perfectly the masking edge's sharpness or blurriness against the surrounding imagery. In essence, this is how you can avoid that fake-looking cutout "collage" feeling in a composite. If the masking edge of an object is sharper than the sharpness of the images around it, the composite will look wrong to our eyes. The same principle applies if the masking edges are too blurred compared to the surroundings—sadly, we see this all the time; it's called bad compositing, or sometimes termed collage art. (Oh, slam!) For seamless compositing, look critically at the edge along the layer you're masking. If you see a blur of two pixels on the image itself, make sure that the masking has a similar feathering around its edges.

Match Lights and Darks Before Matching Colors

Back to that jigsaw metaphor I mentioned earlier: Combining disparate imagery can be quite tricky, to say the least. To help with knitting together two very different shots, start by matching the lights and darks. Changing the lights and darks of an image will invariably change the coloring and everything else in some way, so it's a good idea to start with a Curves adjustment layer to get the values matching nicely before moving on. (By the way, values is just "art speak" for lights and darks.)

Even taking shots with the same general setup can still give you different coloring sometimes, especially when dealing with natural light and a partly cloudy day—working with clouds is simply a pain! Once your lights and darks match up, changing the coloring is often a good idea. There are a zillion different ways to do this (as with nearly everything in Photoshop), but my favorite is to use a fast-and-easy Color Balance adjustment layer. With very little slider movement, this adjustment will let you get things pretty close to perfect a majority of the time.

The other adjustment I often use in tandem with a Curves adjustment layer is a Hue/Saturation adjustment layer. This technique lets you compensate for the increased saturation that often accompanies playing with the lights and darks of an image. Add one of these adjustments, clip it to the same layer as the Curves, and then desaturate with the desaturation slider until the image meshes seamlessly with its surroundings.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Obviously, a great deal more is involved in compositing than what I've briefly discussed in this article, but I hope you've found these tips to be helpful. If you're interested in an entire book filled to the brim with great ideas, check out Adobe Master Class: Advanced Compositing in Photoshop, in which I build on lessons and tutorials for a wide range of composite styles and ways to have pure, addictive digital fun.