- Memory In & Out

- Types of Memory

- Repetition and Memory

- Summary

Types of Memory

So far, we’ve been talking generally about the way a stimulus gets encoded into long-term memory, but there isn’t just one general type of memory. There are actually several different types of memory that are encoded and retrieved in distinct ways. Some types of memory will be more appropriate to focus on, depending on your subject matter, and learning design can often benefit from taking advantage of different types of memory.

There’s a well-known story in psychology about an amnesia patient who did not have the ability to form new explicit memories. Her doctor had to reintroduce himself to her every time they met, because she couldn’t remember him from day to day.

One day, as an experiment, the doctor hid a small sharp object in his hand when he shook the patient’s hand in greeting.

When he followed up with her later, she had no explicit memory of meeting him, and needed to be introduced to him yet again, but when he offered his hand, she didn’t want to shake it, even though, when asked, she couldn’t give any reason for her reluctance.

This suggests that memories are processed in different ways, and that people are not consciously aware of all their memories.

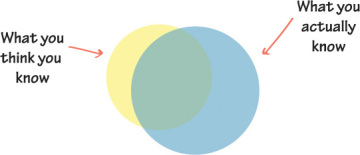

What you know you know—The overlapping area (above) is your explicit memory. You know it and you know you know it, and you can talk about it if needed.

What you don’t know you know—The rest of the blue area is your tacit memory. You know it, but you couldn’t describe it in any detail or talk about it in a meaningful way. Sometimes it is things you forgot you knew, and other times it is things that are encoded in memory without your conscious awareness. You don’t need to be an amnesiac to have tacit knowledge.

What you only think you know—The yellow area is made up of things you only think you know, but when you try to use those bits, your knowledge is incomplete or reconstructed incorrectly. Everybody has this—it’s part of the messy human cognition process.

Within these categories, there are many different types of memory. We are still very much in the process of understanding how different types of memory work in the brain, but some of the types of memory include:

- Declarative or semantic memory. This is stuff you can talk about—facts, principles, or ideas, like WWII ending in 1945 or your zip code.

- Episodic memory. This is also a form of declarative memory, but it’s specific to stories or recollections from your own experience, like what happened at your graduation or when you started your first job.

- Conditioned memory. Like Pavlov’s dog, we all have conditioned reactions to certain triggers, whether we realize it or not, like when a pet gets excited about the sound of the can opener that precedes getting fed.

- Procedural memory. This is memory for how to perform procedures, like driving a car or playing the piano.

- Flashbulb memories. We seem to have a special type of memory for highly emotionally charged events, like national catastrophes.

Each different type of memory has different characteristics and different applications.

Declarative or Semantic Memory

Declarative memory is mostly the stuff you know you know and can state explicitly, like facts, principles, or ideas.

Sometimes it’s stuff you put into your closet deliberately (multiplication tables, for example), and sometimes it’s material that you know despite not having made any conscious effort to retain it (everything I know about Britney Spears, for example).

Episodic Memory

Episodic memory is also a form of declarative memory, in that you can talk about it, but it’s related to specific events or experiences you’ve had.

For example, you may be able to remember a lot of things about dogs—they are pets, they have four legs, they are furry, they eat dog food, Scooby-Doo is a dog, and so on.

But you also probably have episodic memories about specific dogs that you’ve known—your childhood dog, the neighbor’s dog, or the scary dog that followed you to school when you were little.

Storytelling

Episodic memory refers specifically to our memory for things that have happened to us in our lives, but even when a particular story didn’t happen to us personally, we seem to have a singular ability to remember stories.

At the beginning of their book Made to Stick, Chip and Dan Heath compare two passages. The first is an urban legend (a man meets a woman in a bar and wakes up later in a bathtub full of ice with a kidney missing), and the second is a paragraph about the return-on-investment rationale for non-profit organizations (or something like that).

A few years after reading the book, I can still remember several salient details from the urban legend and nothing at all about the second passage. There are multiple reasons why that’s the case, but a big part of it is because the first passage is a story.

There are a few reasons why stories seem to stick in our memories:

- We have a framework for stories. There’s a common framework for stories that we’ve all learned from the first stories we heard in childhood. Whether we realize it or not, in each culture there are common elements that we expect to hear when someone tells us a story. There’s a beginning, middle, and end. There’s the setup, the introduction of the players, and the environment. There’s The Point of the story, which is usually pretty easy to recognize when it comes along. These are all shelves in our “how storytelling works” closet that give us places to store the information as we encounter it.

- Stories are sequential. If I tell you 10 random facts about tennis, you need to expend mental energy trying to organize those facts somehow, possibly grouping like items or using some other strategy. If I tell you the story of a particularly gripping tennis match with 10 significant events, then the sequence of events provides a lot of the organization for you. Additionally, there’s an internal logic to events in stories (logically, dropping the carton of eggs can’t happen before the trip to the grocery store in the story of having a bad day).

- Stories have characters. We have a lot of shelves to store information about people, their personalities, and their characteristics. If the story is about people we know, then we have all that background information to make remembering easier, and we have expectations about how they will behave. And if the character confounds your expectations by acting in a way that conflicts with your assumptions, that is surprising and novel and subsequently more memorable.

Which of the following would you be more interested in learning more about?

Conditioned Memory

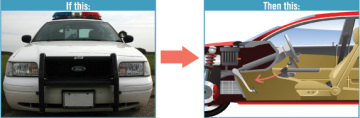

So you are cruising down the highway, and you glance in your rear view mirror and see a police car right behind you. Pop quiz—what do you do?

You slow down, right? Even if it becomes immediately apparent that the cop isn’t the least bit interested in you, you’ve already dropped your speed, even if you weren’t speeding in the first place.

What’s happening there? Probably you didn’t think to yourself, “Hmm, there seems to be a police officer behind me. Perhaps I should reduce my speed! I think I’ll just gently let up on the gas pedal...easy does it...”

No, it was probably something more like, “WHOA!!” and you stomped your foot on the brake.

You see the stimulus of the police car, and you have what is a pretty much automatic reaction to what you see. This is what is referred to as a conditioned response.

Our conditioned responses are a form of implicit memory. Somewhere, stored in a part of your brain that you don’t necessarily have explicit access to, there’s a formula like this:

Everyone has reactions ingrained in their memory. Many are useful reactions acquired either through unconscious association or through deliberate practice:

Some actions didn’t need much effort to encode (like recoiling from a snake). We acquire others deliberately, through practice and repetition.

Procedural Memory

Procedural memory is our memory for how to do things. Specifically, it’s our memory for how to do things that require a step-by-step process.

Some of the procedures you know are consciously learned, and you can explicitly state each step, but a lot of procedural memory is implicit.

Have you ever:

- Known how to get somewhere, but been unable to give somebody directions to that place?

- Gotten all the way home on your daily drive from work and realized that you have no memory of the drive itself?

- Been unable to remember a phone number or a PIN without tapping it out on the actual keypad?

- Thought you explained all the steps for a task to someone and then realized after it didn’t work that you had neglected to mention some crucial details?

Those are all examples of utilizing something in your unconscious procedural memory. You use repeated practice of a procedure to make it become an unconscious habit. This is pretty important because it frees up your conscious attention to do other things.

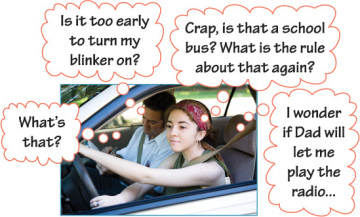

Do you remember when you were first learning to drive? Everything required effort and attention.

Even if you were a pretty good student driver, you were still a bad driver, because you had to pay so much attention to everything until you acquired enough practice to start automating some of the steps. Attention is a finite resource, and new drivers spread it pretty thin. Fortunately, they start automating functions pretty quickly and can then allocate a bigger chunk of their attention to things like not crashing, or avoiding pedestrians.

When you’ve been driving for a while, you (presumably) have freed up a lot of your attention for other things besides the basic mechanics of driving, so you can then, for example, change the radio station while switching lanes and sing along at the same time. Of course, you may still be a bad driver years later, but that’s probably due to other issues.

Automated procedural memory is related to the idea of muscle memory, which, despite the name, is still really a brain function. Muscle memory refers to your procedural memory for tasks you have learned so well through practice that you don’t have to put any noticeable conscious effort toward them.

You get muscle memory through practice, and more practice, and even more practice (a process called overlearning). The biggest benefit of this is that you can perform the task without using up your conscious brain resources, freeing up those resources for other things.

It’s frequently difficult to talk to others about these kinds of tasks, because you didn’t learn them in a verbal, explicit way. You may know exactly how to adjust your golf swing to account for wind conditions, but you may not be able to explain it clearly to someone else. You can probably explain the overall motions, but not the subtleties (timing, how much pressure, the feel when you know it’s correct).

Flashbulb Memory

A few years ago, a freeway bridge near my home collapsed during rush hour, causing the death of about a dozen people and injuring over a hundred more. It was widely reported in the national media at the time.

I vividly remember where I was when I heard about it. I was in a meeting room at the office working on a conference proposal. The lights were dim, and one of the cleaning people came in and told me about the bridge. I remember what chair I was sitting in, all the details of the proposal I was working on, and which website I used to get more information about the incident.

This type of vivid memory for emotionally charged events is call flashbulb memory. It’s common for people to be able to recollect exactly where they were when they heard about the September 11th terrorist attacks, for example.

So what is the cause of this type of memory, and what does it have to do with learning? (Not that staging a major newsworthy event is a practical way to encourage retention.)

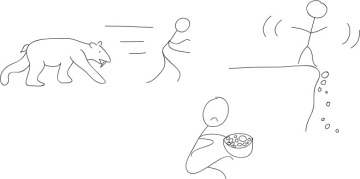

Many believe that flashbulb memory developed as part of our brain’s attempt to keep us alive.

If you survive a death-defying encounter, you want to remember how you did it. Remembering how you got away from the bear is a much higher survival priority than remembering where you left that rock. You can forget all sorts of day-to-day things without dying, but if you bump into a bear a second time, forgetting key information from your first encounter may get you killed.

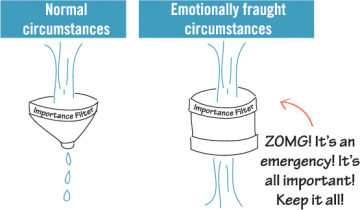

Ordinarily, it takes time, effort, and repetition to get things into your long-term memory, but in emotionally charged circumstances the floodgates open and take in everything in the timeframe around the event. Sometimes it seems like time stands still.

One theory about why time seems to slow in an emergency is that you just remember so much more from those harrowing seconds than you do from the same amount of time in a normal circumstance. (Stetson 2007)

Even though I have never been personally harmed or threatened by an event like a bridge collapse or a terrorist attack, the heightened emotional charge of just hearing about the event seems to be enough to enhance my memory.

Even in less dire circumstances, emotion seems to have an impact on how much we remember. We will revisit this idea in later chapters and look at specific methods for using emotion to enhance retention.